Differentiation and 'Stretch and Challenge' Lecture

Introduction

This chapter addresses two related concepts: differentiation and 'stretch and challenge'. The chapter first defines and introduces differentiation as a classroom concept which has relevance for educationalists at all levels in providing meaningful and productive engagement with new knowledge and skills for learners. It goes on to discuss why differentiation is relevant, indicates some strategies which may be of use in developing your competencies in this area, and discusses also the limitations and the positives associated with differentiation.

The chapter moves on to discuss the allied concept of 'stretch and challenge' in more detail, and focuses on the issues and opportunities associated with supporting abler learners. Strategies for 'stretch and challenge' are discussed, as are rationales for furthering this agenda. Throughout the chapter, there are opportunities for you to reflect on your own educational experience, and think about how you can implement these strategies through your practice. A 'hands-on' scenario at the end of the chapter exemplifies, in a case study format, some of the issues and challenges for teachers which may be involved in planning and delivering a differentiated lesson.

Learning objectives for this chapter

By the end of this chapter, we would like you:

- To understand and be able to explain clearly what 'differentiation' means

- To identify different methods of offering differentiation in the classroom

- To evaluate the benefits and drawbacks of differentiation for teachers

- To understand and be able to explain clearly what 'stretch and challenge' means, and how it differs from 'differentiation'

- To critically evaluate the need to offer 'stretch and challenge' to abler learners

Get Help With Your Education Essay

If you need assistance with writing your essay, our professional education essay writing service is here to help!

What is differentiation?

Differentiation refers to how we, as educators, ensure that the full spectrum of all learners' potential is engaged with and supported, by providing input and supportive learning activities which are suited to the needs of each pupil. The term acknowledges a shift away from a view of education as being fundamentally teacher-centred - where the didactic educator transmits outwards to the class, and every learner treated as though they were equal in respect of their abilities and interests - towards one which is learner-centric, and where different pupils' educational experiences are curated, so that though there is commonality in the class in terms of what is studied, there is both acknowledgement and appropriate support for the ability range across the cohort. This may mean, for example, a selection of activities and tasks being incorporated into a single lesson to best engage learners at differing ability levels. Differentiation also calls for a suite of pedagogic approaches and communication strategies being articulated by the teacher to best support pupils across the ability range (Tomlinson, 2004).

Tomlinson (2004) sees six factors as relevant for teachers to be properly responsive to the needs of all their learners:

1. The teacher should focus on clarity when explaining the essentials of the topic under consideration in the session; this is beneficial because the basics are covered clearly so that less able learners can engage, but the brevity of the input means that abler learners are not disengaged by protracted explanations of concepts they have grasped straightforwardly.

2. The teacher should be attuned to student difference in the differentiated classroom. This is not only in the more formal aspects of task completion and assessment, but in tone of voice, mode of address, and use of questioning, for example. Teachers are at their most effective when communicating meaningfully with learners, and that means personalising their interactions to the learner, rather than expecting the learner to keep a certain pace.

3. Assessment and instruction should be linked together; assessing learners, be that in end-of-session summative work, or in informal questioning and answering, is an ongoing diagnostic tool, and the teacher is thus better informed to modify the ways in which teaching is differentiated, because of such interactions.

4. The teacher should be prepared to modify the lesson in terms of its content (the topic of the session, and the support materials being used to communicate and embed the fresh learning), its processes (the learning strategies employed by learners in engaging with the session and its objectives), and its products (the outcomes, and the tasks and activities employed to evidence those outcomes in learners).

5. A flexible approach by the teacher in respect of content, process and product is articulated with adaptability towards the learners. Tomlinson (2004) sees three aspects of the learner as being of relevance here: first of these is their readiness to engage with a given topic or concept; second, their general level of interest in the wider subject area; and third, their learning profile, which incorporates ideas such as student learning styles.

6. Finally, it is key that learning is conducted in a mutually-respectful and collaborative environment. Where an array of abilities, learning profiles, and engagement levels can be respected, the session can be conducted in such a way that allows for the maximum participation and achievement for all. Fostering such an environment is teacher-led, but needs buy-in from learners, too.

Reflection

Think back to your own education. Can you recall instances of memorable teachers who differentiated effectively in class? Or of those who delivered the same lesson to all? What were the differences in how you engaged with them and the subjects they taught?

To what extent may differentiation come naturally to you as a communicator? How might that be displayed in a classroom context?

Why do we differentiate?

Forms of differentiation have been in existence for as long as there have been schools large enough to require more than one class. Typically, learners have been separated on the understanding that there is a general level of comparability which relates to age and ability terms. Particularly in secondary education, streamed ability classes - sometimes called 'sets' - have long been used to group together learners of approximately equal abilities. In such relatively crude ways, there can be differentiated educational experiences through separating larger bodies of learners into smaller teaching groups, and then teaching more tailored content to those groups.

In contemporary education, though age and ability streaming is still in existence, a differentiated experience more usually refers to a nuanced approach within the class by the teacher. Differentiation offers a way to personalise learning, and in so doing, making learning meaningful to individuals. If the lesson has meaning, and the topics are communicated in ways that engage and interest learners, backed up with appropriately-selected tasks and activities of an equally-appropriate level of difficulty, then students can be engaged actively in their own education.

For Petty (2009), differentiation reflects developments in pedagogic thinking and its prevalence shows how far education has moved on; that is, the shift from a teacher-centred to a learner-centred focus to the contemporary classroom. We teach not so that we can express our own expertise, but to foster meaningful engagement in others with that taught subject. Petty (2009) suggests that all teaching is informed by differentiation in some way, and that the ways in which an educator can modulate their engagements with learners, and offer assessment and activity opportunities that are creative and appropriately challenging within the bounds of the topic and the level of study are a marker of that teacher's excellence. Differentiation offers the most appropriate way of engaging all learners at a pace and a level that challenges without causing impossible levels of confusion, delivering this in ways that make sense to the learner. Fundamentally, we differentiate so that others may learn best.

Petty (2009) suggests that differentiation may be considered in respect of the kind of task being offered, the outcomes being sought, and by the amount of time allowed to the learner for successful task completion: "[i]t is what the learner does, not what the teacher does, that creates learning, so the task is key. Remember that some learners need more time than others" (p. 587). Task-based differentiation may be the most straightforward form of providing alternate, graduated learning experiences, but it is not the only method which may be used.

Differentiation does not necessarily mean providing alternatives, though. Careful consideration in advance of tasks and outcomes can lead to the devising of activities which accommodate a breadth of different learning styles and approaches to study (Petty, 2009). A broad brief, which is open to interpretation, for example, may suit a diversity of responses at different levels. Similarly, group tasks and exercises where peer learning and peer assessment are involved can engage and support differentiation in the classroom. Problem-solving exercises, and activities demanding creativity in their completion, will generate student-led differentiation through the varied responses to the task. Another way in which learning may be differentiated is in individualised learning, and the setting of personalised targets and activities for specific learners. Students may be given individualised instruction, often to support the initial class-wide input, or else be given activities and tasks which are designed to support them and their specific educational needs (Petty, 2009).

Differentiation may occur, then, in respect of: task; grouping; resources used; pace of learning or of task completion; having varied outcomes; moderating dialogue and support with learners; assessment methods and targets (BBC Active, 2010). Methods can be combined and varied to suit the needs of learners in the class, particularly regarding their learning needs, abilities, and preferred styles.

Reflection

What engages you as a learner? How might that differ from your peers? If you were teaching yourself, how would you approach you as an individual, and how might that differ from others in your peer group?

What are the benefits and limitations of differentiation?

There are both clear advantages and potential drawbacks in providing a fully-differentiated classroom experience for learners. This section indicates several benefits and issues associated with differentiation.

Advantages (Lombardo, 2016):

- Differentiation offers each learner the opportunity to excel to the best of their ability.

- Differentiation promotes equality and diversity, as all learners are given individual consideration rather than focusing such attention on those whose circumstances might demand it (such as learners with SEND).

- A differentiated approach focuses attention on the learners and on their needs, rather than on the subject or on the teacher. This makes teaching fresh, and a new and meaningful challenge is provided with presentation of each topic.

- Differentiated strategies privilege flexibility and creativity in the teacher; teaching and communicative expertise is both showcased and scrutinised on a continual basis.

Disadvantages (Layton, 2016):

- There may be workload issues for the teacher in the planning and preparation of fully-differentiated classes, and associated administrative burdens in recording learner progress.

- Differentiation relies on learner buy-in. Reluctant learners, obstructive students, or those who may not be able to grasp a concept may still take up teacher time and skew the session towards them.

- Judgment on where to draw lines between whole-class progress and differentiated learning may prove awkward to manage at the scheme of work level, necessitating frequent re-planning.

- It may be difficult to assess the success of a fully differentiated strategy against the abilities of learners in and of themselves.

- Time constraints in-class may limit the scope of possible differentiation strategies which can be realistically deployed.

The advantages of differentiation outweigh the limitations, but teachers should be aware of the practicalities of articulating the needs of the individual learner against the needs of the class. Strategic planning to maximise opportunities ahead of time should be combined with the seizing of live chances in the teaching moment to best support the diverse needs of learners.

Reflection

Look again at the list of benefits and drawbacks given above. To what extent do the drawbacks pose real problems to you as an educator? To what extent do the listed benefits provoke opportunities for you?

Can you think of further limitations to add to the list? What about other potential advantages?

What is 'stretch and challenge'?

We can think of the term 'stretch and challenge' as encompassing two separate though related, aspects to classroom practice, both of which have connections to differentiation. In the first instance, 'stretch and challenge' may be conceptualised as referring to the provision of a whole-class experience that underscores the relevance of providing stimulating tasks and activities that push all learners to the limits of their current knowledge and educational comfort zones. In the second, and perhaps more readily-understood version, the term 'stretch and challenge' refers to the most able learners in any group, and the provision of an educational experience that allows them to achieve at the outer limits of their ability, and perhaps beyond the aims and objectives of the lesson plan.

For learners of different abilities within a class, 'stretch and challenge' might mean different things. What is central to the concept, though, is that each learner is challenged to the outer limits of their ability. For many learners, this may mean that such challenge is represented within the tasks and activities provided for the session. For gifted and talented learners, or for those who are simply engaging well with the topic under consideration in the immediate teaching session, it may mean that additional strategies need to be in place to provide further exploration of the topic, or to trigger performance at a higher or more detailed level in activity-based learning.

For the teacher, then, the question of stretch and challenge requires consideration in two ways: first, that all learners are stimulated to their maximum, and that there is preparation in advance should additional learning opportunities be relevant for learners who would otherwise comfortably exceed the parameters of the lesson. This section, and the one which follows, focuses on achievement at the higher end of the class ability; however, it is to be recognised that the principles behind 'stretch and challenge' should apply equally to all learners.

Your setting may well have a policy that formalises its approach to 'stretch and challenge'; a link to an exemplar policy is the reference list at the chapter's end. Such policies will make clear the setting's position on the relevance to whole-school learning, to differentiation, to diversity, and to inclusionary practice embedded in its approach to 'stretch and challenge' (Thomas Tallis School, 2015).

'Stretch and challenge' also acknowledges a difficult truth about teaching: that sometimes, attention may be unequally focused on those learners who require support, offer behavioural and attitudinal challenges, and who may reside at the lower end of the ability range in the class. Effective deployment of 'stretch and challenge' redresses that balance by offering not only a reminder of the responsibility to all learnerrs, but a set of practical tools to support that realisation; higher-achieving learners should not to be left to get on with their other work, or because theydo not need the teacher's help, they can be safely left alone. All learners deserve to have their potential tested and encouraged in positive and supportive ways. 'Stretch and challenge' is the mechanism by which this may be both done and evidenced.

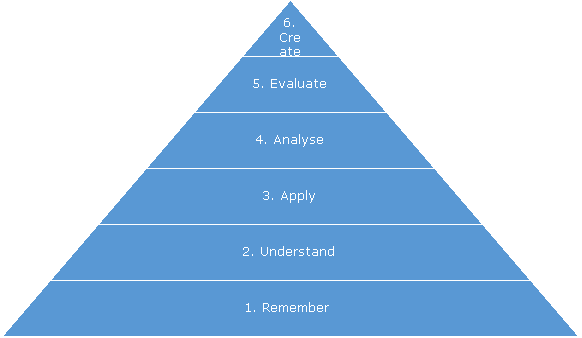

At its simplest, then, 'stretch and challenge' means the provision of additional learning materials related to the topic in question which further a learner's investigation of that topic. Typically, this will be at the upper end of the class ability range. Additional activities should not simply be more of what the learner has already done, but seek to develop the learner's skills, competencies, and exploration of the topic area. One tactic is to use Bloom's taxonomy to differentiate the approach taken to the subject, by provoking investigation at a level higher than what has gone before.

Graphic: Bloom's taxonomy (Teachervision, 2016)

As an example, if a topic has been studied in the session at the level of application (with the lesson plan using verbs such as "demonstrate", "solve", "show", and "examine", for example) then a suitable 'stretch and challenge' extension activity might step up the taxonomy to the next level - analysis - and re-engage with the topic area accordingly (verbs such as "explain" and "compare" in the lesson plan) (Teachervision, 2016).

Reflection

Does your institution have a policy on gifted and talented learners and/or on 'stretch and challenge'? Find out, and if so, read that policy/those policies. If no such policy exists, why might that be?

Does your institution have a point of contact for gifted and talented learners? Are there assessment procedures in place? How might your institution's approach to its abler learners differ or match the ways in which comparator institutions address this topic?

Get Help With Your Education Essay

If you need assistance with writing your essay, our professional education essay writing service is here to help!

Why do we 'stretch and challenge' learners?

As the previous section has outlined, it can be sensible to think of 'stretch and challenge' as a formalised way of providing extension activities to advance the engagement of learners at the higher end of the ability range. However, this should not be thought of as something to be done for its own sake, or to simply keep learners busy and thus not becoming a distraction to others still working to complete activities. There is a substantial body of literature supportive of the concept of stretching and challenging, which indicates how and why it is vital for a truly inclusive and engaging classroom practitioner to be able to provide a stimulating and appropriately thought-provoking educational experience for all in the class. This section offers a few such examples, before moving on to offer a way of conceptualising 'stretch and challenge' in practical terms.

A 2013 Ofsted report noted with disappointment that too many abler learners were underachieving in that, though they were exceeding national performance averages, they were not being stimulated to activating their full potential as students; shortfalls of this kind were observed at in both primary and secondary educational contexts (Ofsted, 2013). Underachievement of high-attaining learners was also identified at GCSE and at A level in the same report (Ofsted, 2013). Ofsted noted that there were ramifications for this in terms of individual educational achievement, but also with respect to wider considerations, such as the UK's broader ability to be economically and intellectually competitive in global terms (Ofsted, 2013).

The report noted that successful schools tended to promote achievement in several ways: these included fostering a culture of high expectations and of high aspirations for their learners, and by establishing "clear expectations that high-attaining students would achieve their goals, for example by ensuring that the most able students were given challenging and stretching targets" (Ofsted, 2013, p. 21).

The same report summarised good practice, which was commonly observed in the best-performing schools (Ofsted, 2013). Relevant strategies in supporting abler learners included:

- Staff having detailed knowledge of their abler learners, and of their relative strengths and personal interests as learners

- Having rigorous and challenging programmes of formative and summative assessment

- Using tracking and monitoring strategies to maintain a focus on abler learners, and to intervene supportively if a decline in performance is detected

A 2007 report from the (then-titled) Department for Children, Schools and Families focused on how to ensure effective provision for gifted and talented secondary school learners. By 'gifted and talented', the report considered "those young people who are achieving, or who have the potential to achieve, at a level significantly beyond the rest of their peer group. This refers to the upper end of the ability range in most classes/cohorts" (DCSF, 2007, p. 8).

The report noted that central to such effectiveness was offering learners work which would continually stretch and challenge them, while supporting such challenge through providing a positive school environment where excellence was cherished (DCSF, 2007). This report linked the detecting and nurturing of potential in pupils with the provision of additional and bespoke learning opportunities, and the support to make the most of those opportunities, combined with enthusiasm and drive to succeed as being the factors which should combine to generate high levels of learner achievement. The report also commented on links to be drawn to wider educational and equal opportunities agendas.

From sectoral skills reviews, to the enjoyment and achievement mandate of Every Child Matters, to a selection of government publications investigating inclusionary and individualised learning protocols, the support of able learners through 'stretch and challenge' is seen as necessary and proper in a contemporary education system (DCSF, 2007).

In practical terms, when considering the level of stretch and challenge to offer learners, the following may be of use. Imagine that there are three possible zones of engagement with a topic:

- The comfort zone: characterised by low stress, little or no challenge to the learner, limited need to think, and so limited learning is actually taking place

- The struggle zone: Work here is not stressful, but it is challenging. The learner is challenged to think, and so is being stretched; effective learning is taking place.

- The panic zone: The level of challenge here is high, but so is stress, because the activity demands cognitive abilities beyond the current reach of the learners. Limited or no learning is taking place.

The zone to target for your learners is, in this model, the struggle zone (Teacher Toolkit, 2016). If the standard activities and tasks are well within the comfort zone of the learner, then they are not learning. Producing additional or alternative tasks which fall into the struggle zone means that the learner must work to achieve, but the task is not impossible for them.

Reflection

What can you do better as an individual to support and stimulate your most able learners? What can your institution do in this regard?

This section has drawn examples from a top-down examination of the topic, taking its insights from Ofsted and other governmental publications. From the learner's perspective, though, how and why might such 'stretch and challenge' approaches be of benefit?

Conclusion

This chapter has covered the related areas of differentiation and 'stretch and challenge'. Providing an appropriately differentiated learning experience has been shown to be central to contemporary education. However, there are always practicalities to address, and a fully-individualised class is perhaps beyond the bounds of all but the most exclusive of educational establishments. Don't feel concerned that you can't do everything for everyone; think instead about how you can maximise learning opportunities through appropriate levels of differentiation. Think smart, rather than working to extremes.

The chapter has tried to indicate that there are many ways to differentiate, and that differentiation is not necessarily all about the personalised, but it is about matching teaching and assessment approaches to learners in meaningful and productive ways across the ability spectrum. The challenge is to make each lesson as differentiated as practicable, and then determining what the appropriate limits of that customisation are.

Reflection

Now you have completed this chapter, you should:

- Understand and be able to explain clearly what 'differentiation' means

- Be able to identify different methods of offering differentiation in the classroom

- Be able to evaluate the benefits and drawbacks of differentiation for teachers

- Understand and be able to explain clearly what 'stretch and challenge' means, and how it differs from 'differentiation'

- Be able to critically evaluate the need to offer 'stretch and challenge' to abler learners

Reference list

BBC Active (2010) Methods of differentiation in the classroom. Available at: http://www.bbcactive.com/BBCActiveIdeasandResources/MethodsofDifferentiationintheClassroom.aspx (Accessed: 31 October 2016).

Department for Children, Schools and Families (2007) Effective provision for gifted and talented students in secondary education. Available at: https://www.learntogether.org.uk/Resources/Documents/Effective%20provision%20for%20GT%20students%20in%20secondary%20education.pdf (Accessed: 31 October 2016).

Department for Children, Schools and Families (2009) The classroom quality standards for gifted and talented education: a subject focus. Available at: http://www.ttrb3.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/The-Classroom-Quality-Standards-for-Gifted-and-Talented-education-A-subject-focus-flyer.pdf (Accessed: 31 October 2016).

Layton, S. (2016) The pros and cons of differentiated instruction. Available at: http://www.aeseducation.com/2016/03/pros-and-cons-of-differentiated-instruction/ (Accessed: 31 October 2016).

Lombardo, C. (2016) Pros and cons of differentiated instruction. Available at: http://www.visionlaunch.com/pros-and-cons-of-differentiated-instruction/ (Accessed: 31 October 2016).

Ofsted (2013) The most able students. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/405518/The_most_able_students.pdf (Accessed: 31 October 2016).

Petty, G. (2009) Teaching today: a practical guide. 4th edn. Cheltenham: Nelson Thornes.

Teacher Toolkit (2016) 'Lesson planning: the big picture versus the small details', Teacher Toolkit, Available at: http://www.teachertoolkit.me/2016/03/03/lesson-planning-cpd/ (Accessed: 31 October 2016).

Teachervision (2016) Bloom's Taxonomy: An overview. Available at: https://www.teachervision.com/teaching-methods/curriculum-planning/2171.html (Accessed: 31 October 2016).

Thomas Tallis School (2015) Stretch and challenge policy 2015 -16. Available at: http://www.thomastallisschool.com/uploads/2/2/8/7/2287089/final_stretch___challenge_policy_2015-16.pdf (Accessed: 31 October 2016).

Tomlinson, C.A. (2004) The differentiated classroom: responding to the needs of all learners. London: Pearson.

'Hands on' scenario

Question

You are teaching a Year 10 class who evidence a wide ability range, from those who struggle with the fundamentals at GCSE level, to those who already show that their abilities easily exceed the curriculum requirements at GCSE level. Three sample learners are sketched below. How might you draw upon your understanding of differentiation and 'stretch and challenge' to best address the needs of these three learners?

Fiona has been identified as a gifted and talented learner. She is articulate, she is a fast learner who relishes detail, and she thrives on exceeding the given brief in any learning situation. If anything, this represents an issue from a class management perspective - she always finishes her work early, which can be a disincentive and a distraction to others, as well as indicating that she is being inadequately challenged by her GCSE studies.

Peter is an average learner in ability terms for this class, though sometimes shows flashes of real insight and engagement. His performance in tasks and activities can be unpredictable; sometimes he does enough to get by, other times he pushes himself and completes work accurately, quickly, and with some accomplishment.

Mishal is at the bottom of the ability range in this class. She is a trier, and her work indicates that she does her best to engage, but she is sometimes frustrated by her patchy ability to engage with difficult topics. This can sometimes make her irritable, which means she can distract both herself and others around her.

Answer

First, consider the extent in advance that your lesson and its support materials address the needs of all learners. For example, are your materials fully inclusive, reflecting equality, inclusiveness, and differentiation in themselves? Are your input materials (slides, handouts, other resources, your speaking notes) clear and to the point? Brevity and clarity aids all; there is less room for misinterpretation, the ideas being communicated will have punch and immediacy, and all learners will be engaged. Brevity also means that learners like Fiona, who tend to quickly grasp the concepts being discussed and who assimilate the new information readily, will not be bored by lengthy and protracted explanations aimed at the element of the group which needs more explanation. Clarity and brevity allows for less room for confusion. Those learners who struggle with new concepts, such as Mishal, might have less to be confused about, have less of an opportunity to become lost, and can be approached separately to check understanding as part of your questioning to check for understanding outside of whole-class delivery. A spot-question asked of a learner like Peter might indicate how well he is going to perform today.

In lesson planning, it is sensible to note graduated achievement expectations. Many lesson planning templates offer differentiation in the session's aims and objectives. Often this is staged in this format: "By the end of the session, all learners will be able to… / many learners may be able to… / some learners might go on to…". It makes sense to have tasks and activities graduated in ability terms. If this was a maths session, then there could be ten questions which all learners are to complete, an additional five which are given as a further activity for those completing the session's expectation, and a follow-on activity at a higher level of attainment (invoking a staged progression along Bloom's Taxonomy) for high achievers who require additional 'stretch and challenge'.

Such preparation in advance offers flexibility, and will cater to the needs of all learners in a clearer way that a simple 'one size fits all' activity and assessment methodology. If questions in the set activities tend to the closed variety, consider asking open questions to 'stretch and challenge' learners such as Mishal. In questioning and supporting learners, be thoughtful and considerate to their different needs. If Mishal and other similar learners need additional explanation, then this can be given outside of a whole class environment, as part of checking ongoing task and activity work. Her needs are being better met, she is being given a tailored educational experience, and others' learning is not being disrupted. Peter can be similarly encouraged towards higher achievement. Can he complete the first activity and move onto additional work? If so, how and why is this session appealing to him? If not, why not? Make observations that can feed back into future session preparation, and which can refine your perception of this learner and his needs. How is Fiona progressing? Have you pre-prepared an additional activity which extends her engagement with the topic area? Has this been prepared in such a way that it is clear you have thought about her needs in advance? Do not be caught in simply inventing an activity for its own sake; extension work should have a tailored purpose.

Differentiation draws on competencies across the whole suite of teacher skills. A differentiated session will involve consideration in planning and preparation, moderating your delivery style to better suit individuals, nuanced and responsive questioning techniques, appreciation of learner styles and of levels of learner prior attainment, and an appreciation of the personalities of the pupils in the class. Fully developing such competencies, and the confidence to mix and match them effectively in the classroom takes time. Having staged activities of escalating difficulty is only the most obvious element of providing a differentiated learning experience. However, this is a good place to start, and it offers a way, for each session, for you to reflect on the most appropriate ways to offer a differentiated experience which will make learning meaningful to each pupil in the classroom.

Cite This Module

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below: